The Event

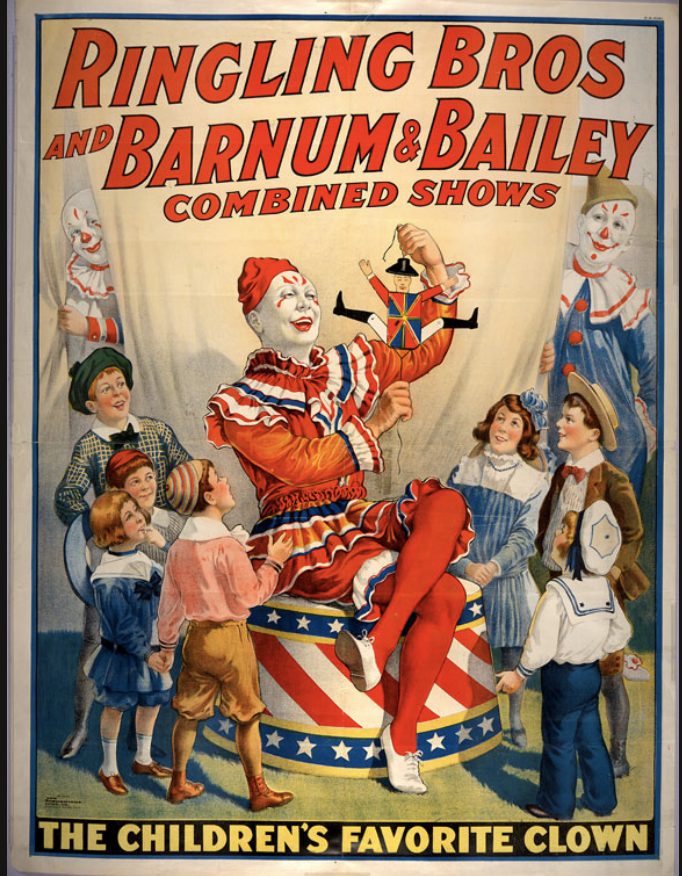

July 6 of 1944 had all the ingredients to be a perfect day. The skies were welcoming, the air was hot, and the Ringling Bros. & Barnum and Bailey Circus were in town. Families flocked to Hartford, Connecticut to see the afternoon show, excited to catch a glimpse of the Flying Wallendas, or the gentle elephants. However, at 2:40 PM, the first sign of tragedy struck: fire, quick-moving and deadly, had begun climbing up the Big Top

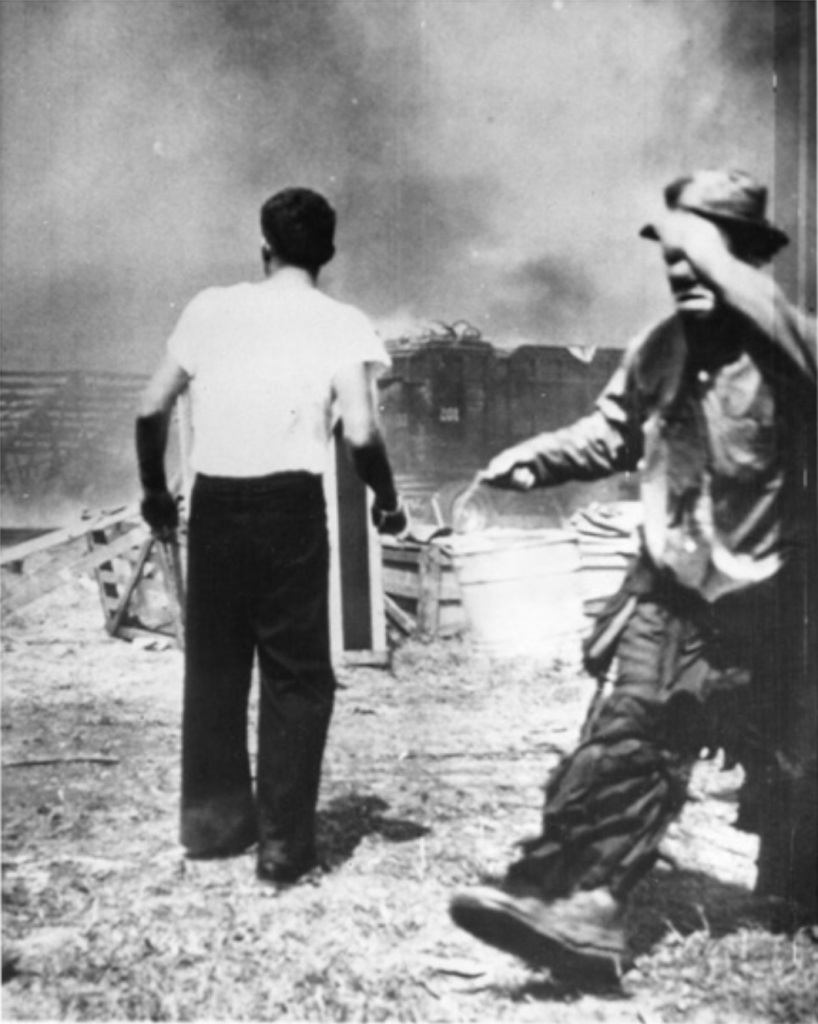

According to witnesses, the fire began as a small one, easy enough to extinguish with a bucket. Soon, the flames evolved into an inferno, eating everything in sight. Ushers desperately attempted to put out the fire, but simply could not do so without being burned themselves. The fire ate its way through the canvas of the big top, starting behind the Blues—which is a bleacher section of the crowd—and only growing with each passing moment. The band played for as long as they could, only ceasing when the fire began to attack them. Within 10 minutes, the exciting family day at the circus was reduced to ash, only leaving behind lost children and hysterical parents. Many attempted to get back into the tent, such as one woman, who yelled in agony “My God… My kid’s in there!” (Berger, 11).

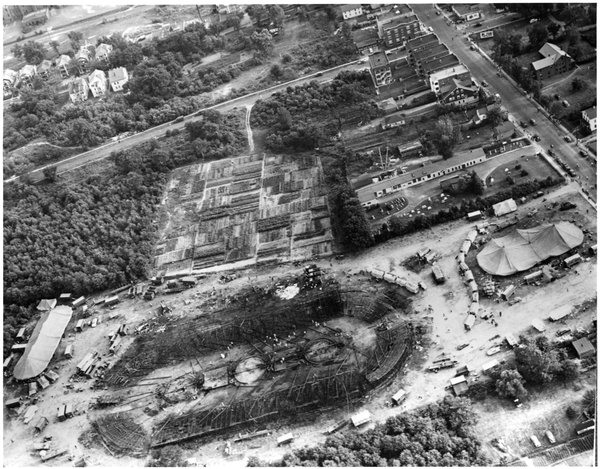

The reason why the flames spread with such speed was due to a dangerous and irresponsible waterproofing method. The canvas was coated in paraffin, diluted with gasoline. This mixture is horribly flammable. One spark or ember would have easily lit the entire tent, which is exactly what happened. Attendees ran, the best they could, to seek an exit point. Unfortunately, due to heavy smoke, many could not see the path to escape, and ended up running right into one another. However, smoke was not the only element hindering the line of sight; the canvas fell onto circus goers in large sheets, covering their heads and eyes. Those that were lucky enough to find a point of exit were sometimes still trapped, as the large masses of victims simply could not fit through the small exit openings. Canvas fell quicker and quicker, burning skin and charring clothing. The fire moved so quickly, in fact, that first responders were virtually powerless to stop it. Response time was impressive, but the flames were simply too quick.

The day after the fire, the New York Times reported 313 casualties, 139 of which were fatal (Berger, 1). However, the numbers changed quickly as more victims were found or recovered, and historians now know the final death count was 168, with between 400 and 600 injurie, as reported in 2019 by Hartford Currant authors Steven Goode and David Altimari.

Burns were, of course, the most common cause of injury, but trampling-related injuries were common; Patrons toppled over one another to escape, desperation rising with every moment. The sheer mass of casualties was, of course, overwhelming, and the Hartford Armory chose to open its doors to accommodate and house the dead. Families lined up, anxious to see if their son, daughter, wife, husband, sister, brother, and so on, were part of the dead. At the time of the New York Times article mentioned above, it was reported that two-thirds of the victims were children. Most of the victims were, in fact, women and children, as many men and fathers were serving in World War II efforts. It was speculated by the New York Times that a carelessly dropped cigarette behind the Blues was what ignited the inferno. However, an alternative version of the story will be explored later in this article.

The Question

How could such a tragedy occur? This was the question that immediately crossed the minds of the victims, their families, and the world. Here, the dominant two theories will be explored in depth.

- The Hartford Circus Fire of 1944 was a preventable and horrible accident.

Or

- The Hartford Circus Fire of 1944 was a destructive act of arson

An Avoidable Accident?

A number of variables perfectly combined to create a dangerous scene on this perfect summer day. The largest variable, and unfortunately unavoidable one, was the immense popularity of smoking. It was not uncommon for cigarette butts to be carelessly tossed aside once the smoker was done, and it would be plausible that this was the case on July 6. This could have been especially possible, due to the worker’s carelessness in not placing “No Smoking” signs around the tent. This gross oversight was only the start.

Another factor was the placing of animal cages that blocked two vital exits of the tent. Blocking these exits meant the difference, not between whether or not the fire occurred, but whether or not patrons survived the flames. Furthermore, the circus chose not to inform the Hartford Fire Department or the Hartford Police Department that they would be in town. This meant that first responders were not only unprepared to provide safety to patrons but were wildly unprepared to provide assistance in the case of a disaster. Once the fire started, it became apparent that the nearest hydrant was 300 feet away, and that the circus’ fire hoses could not be properly hooked up to it. On top of this, as discussed previously, the tent’s waterproofing method was a dangerous, highly flammable mixture. This method was typical during the 1900s, and became the only option during the war effort, as the United States military had all rights to the only known waterproofing method that was also fire-retardant.

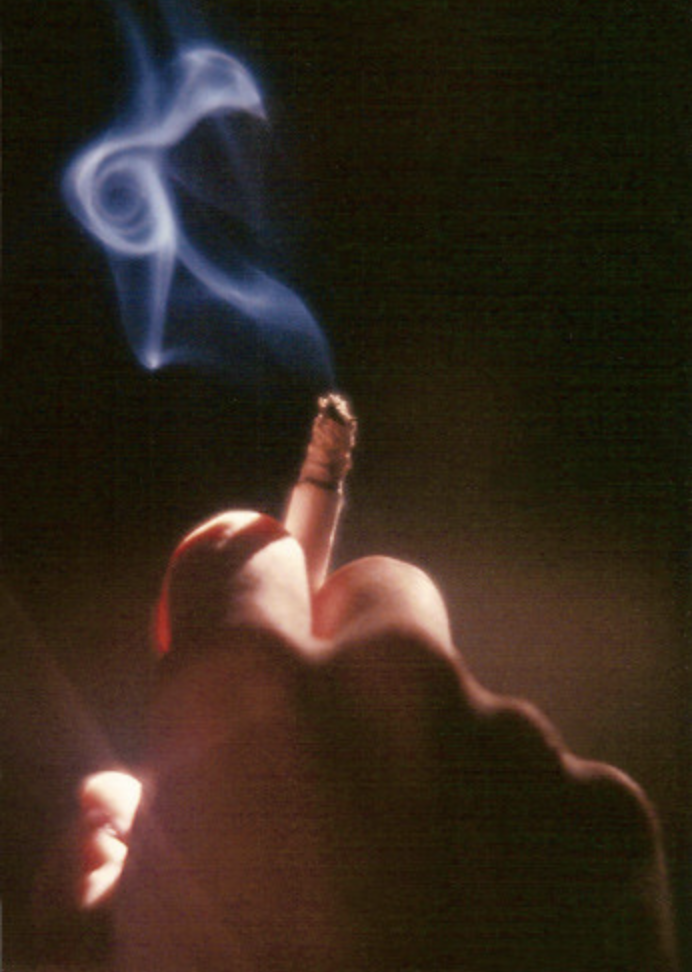

Cigarette Smoke

1944 Hartford Circus Fire Raw Footage

All of this combined to create a recipe for disaster. However, readers may be scratching their heads, wondering: How could all of these oversights occur without being noticed? The simple answer is that the safety inspection never occurred. Author Laura Woollett describes the sequence of poor decisions made by Charles Hayes in her novel Big Top Burning. Building and safety inspector, Charles Hayes, was tasked with checking the big top prior to the start of the circus, all in the pursuit of keeping patrons and onlookers safe. However, when Hayes arrived at the grounds, the circus was hardly set up at all. He decided to return later in the afternoon, as to allow the circus to get set up to completion. When Hayes arrived later in the day, the circus still was not ready. Safety inspections were not mandatory at this time. He claimed that the Ringling Bros. & Barnum and Bailey Circus had always complied with regulations at previous shows, so he assumed this time would be no different. Therefore, he went on his way, giving the circus the greenlight, not knowing exits were blocked and fire hoses were not compatible with hydrants.

All of these unfortunate oversights, combined with the incredibly plausible idea that a careless smoker tossed his or her cigarette aside, easily support the theory that the July 6 fire was a terrible, yet avoidable accident.

An Appalling Arson?

Police commissioner Edward J Hickey investigated the fire in depth, and concluded it was an accident of carelessness. Based on the statement of an unknown witness who stated “some dirty son of a bitch tossed or dropped a cigarette” (Woollett 105), and usher Kenneth Gwinnell, who stated it was awfully common for matches or cigarettes to be carelessly dropped during circus performances (Woollett 106 ), Hickey decided the blaze was the result of a careless smoker (Woollett 110). It added up, in his mind. Arson was simply not up for consideration.

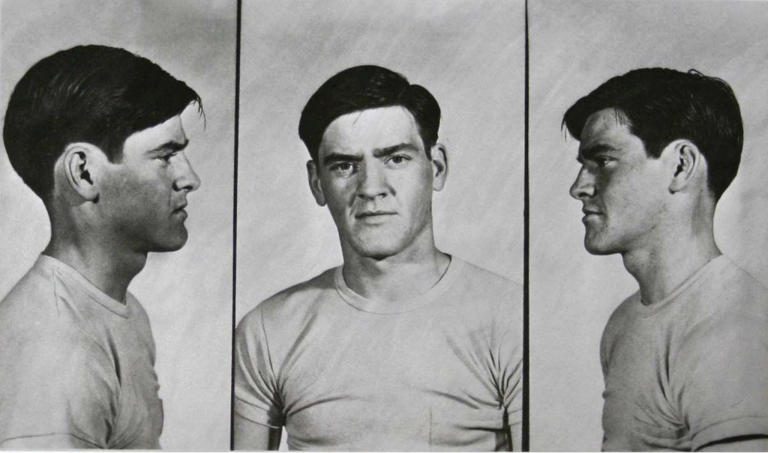

However, in 1950 , after the Hartford Circus Fire case was closed, a confession changed everything. Robert Segee, who was 20 at the time of his confession (and 14 at the time of the blaze), claimed he was the cause of the fire when he was a member of the lighting crew. During a police interview in Circleville Ohio, Segee confessed to setting fires there, in Columbus Ohio, and in Hartford during the 1944 Ringling Bros. & Barnum and Bailey Circus Show.

Segee’s past seemed built to create a criminal, even a pyromaniac. In Woollett’s account about the fire, she reported that Segee’s mother, Josephine, declared that his son grew up in a less than ideal environment. She explained that Segee’s father and Robert did not have the best relationship, which often led to him running out of the house. He walked the streets of his town at all hours of the day and night. He also had night terrors. Eventually, he started roaming the streets at night, all in the pursuit of escaping his nightmares. Josephine told investigators she “knew something was wrong with him… but never wanted to admit it” (Wollett 115). Segee’s sister, Dorothy, painted a similar picture, but claimed that it was common for her brother to act out, and even recalled two instances in which he set fires, the first one being at the young age of 5 (Wollett 115).

Based on his family testimony, psychologically, Segee seemed to fit the profile of a pyromaniac. In this confession, he claimed to experience visions of a Native American man, whom he referred to as “The Red Man” (Wollett 116), in which he was urged to set fires. Segee declared in his declaration that a similar vision had come over him the day of the Hartford tragedy. He explained that after a bad date with a girl downtown, Segee made his way to the circus grounds to rest. He claimed that he saw the strike of the match, followed by The Red Man during a trance-like episode. As the dream progressed, it got more vivid and intense, only interrupted by stranger shaking him awake. He claims he then attempted to help, but at that point, it was too late.

Segee seemed to be the perfect suspect. He had a traumatic childhood, a history of pyromania, and a confession. Just as the pieces began to fall in line, Robert Segee retracted his confession. He claimed he was never on a date with the girl, never went back to the circus to rest, and never even set a fire in his life. He changed his July 6 story to that of hanging out with a friend at a downtown movie there. The Connecticut Police and Fire Department were skeptical about this confession. Although they traveled to Ohio to interview Segee, they reported that they weren’t given access to him, and neither were given any report or information that would confirm the veracity of Segee’s confession. Subsequently, they decided not to charge Segee with arson in the Hartford case (Youth Confess 30). Segee died in 1997, still denying he was the arsonist in the Hartford circus fire (Lohr HuffPost)

The arson theory didn’t die out. Instead, Hartford arson investigator, Lieutenant Rick Davey, became interested in the happenings of the circus fire in the 1980s; 40 years after the first flames were spotted. He grew up in Hartford and could not settle on the theory that a cigarette was the cause of such vast destruction. He collected photographs, witness accounts, and even weather records, and was quickly able to see the fire did not start towards the bottom of the big top, but towards the top. This would easily disprove the cigarette theory. The Connecticut forensics laboratory soon received the findings of Davey, and was able to conclude that the weather was far too humid for a cigarette to be the cause of the fire, and that the grass beneath the bleachers was not burnt, as it would have been if a cigarette had been dropped.

Soon, the pieces began to stack again in the direction of Segee. Further investigation uncovered that the movie he claimed he have gone to, The Four Feathers, was not playing during the time he would have been there. His story changed from having been out with a friend to being alone (Wollett 122). His claim that he had been burned in the blaze was contradicted as well, as he was apparently was not at the scene of the fire at all. In interviews conducted by investigators in the 1980s, Segee became increasingly more paranoid. He claimed politicians set him up as the “perfect patsy” (Wollett, 125) for their campaign, and even insinuated Ringling Bros. set the fire themselves to cash in an insurance money check. Segee also claimed the psychiatrists that originally interviewed him had messed with his mind and forced him to draw The Red Man (Wollett 125). On the other hand, Segee’s daughter, Carla, gave a different explanation for her father’s strange visions, claiming he was considered a shaman in the Native American community—although there is no evidence to support such a claim as Segee and his family were white and not related to any Native American group. According to her, though, a shaman’s visions could be strong enough to feel like a reality, but never realistic enough to be factual. Even if these visions were rather strong, she claimed the encouragements of The Red Man “did not come to pass,” (Woollett 111) therefore making him innocent.

Because of this contradicting statements from Segee, and the fact that no witnesses could place him in the scene of the fire, and there was no enough evidence to support the claim that someone start a fire intentionally , the case against Segee began to, yet again, fall apart. After decades of deliberation, the case was officially closed on September 10 of 1993 and was re-listed as “undetermined” from “accidental” (Wollett 126-127)

Concluding Thoughts

The fire of July 6 of 1944 will remain unsolved, at least for the time being. The 168 lives lost may never receive true justice. However, the individuals lost have not been forgotten or left behind. In October of 2019, two Hartford Police detectives worked together to ensure a final resting place for two fire victims. Sgt. Anthony Rykowski and his brother Mike went to work tasked by the medical examiner’s office to handcraft caskets for the victims after they were exhumed in hopes of identifying them. After efforts failed, it was decided the two victims would be laid to rest, permanently. Together, the brothers spent $250 in an effort to create custom, wooden caskets. Mike describes the difficult task as “a privilege”, and speaks on behalf of the victims with humility, reminding readers it is “only right” to provide the victims a final resting place (Goode, Altamari, Hartford Courant.com). Nevertheless, to this day, rumors are still circulating. In my own household, multiple theories have been considered. Perhaps it was a freak circus accident, or an unknowing child playing with matches. Perhaps, the world will never know.

Worked Cited

Berger, Meyer. “139 Live lost in Circus fire at Hartford: 174 Badly Burned Tiny Flame Wells Up into Sheet of Fire, with Throngs in Big Tent Panic Grips Thousands Burning Folds of Canvas Fall on Struggling Mass—Many Children are Victims the Worst Fire in Circus History which took a Heavy Toll of Lives at Hartford.” New York Times, Jul 07, 1944, pp. 1.

Goode, Steven, and Dave Altimari. “Police Officers: ‘It’s a Privilege’ to Make New Caskets for Two Unidentified Hartford Circus Fire Victims.” Courant.com, Hartford Courant, 24 Oct. 2019, https://www.courant.com/community/hartford/hc-news-hartford-circus-fire-caskets-20191024-r7atrkpyzfblppoqbzu653kfnu-story.html?outputType=amp

“Hartford Circus Fire Aerial, July 1944.” Connecticut Digital Archive, https://collections.ctdigitalarchive.org/islandora/object/50002:910.

Connecticut History.org “The Hartford Circus Fire: Connecticut History”, July 6, 2019, https://connecticuthistory.org/the-hartford-circus-fire/.

Ofgang, Erik. “Accident or Arson? The Hartford Circus Fire, 75 Years Later.” Connecticut Magazine, 24 June 2019, https://www.connecticutmag.com/issues/features/its-been-three-quarters-of-a-century-since-nearly-170-people-were-killed-at-a-hartford-circus-in-one-of-the-deadliest-fires-in-us-history-even-today-the-cause-of-the-blaze-remains-a-mystery/article_86bf74dc-8d36-11e9-b000-5f7e5345c104.html.

Lorh, David. “Hartford Circus Fire: A 67-Year-Old Mystery.” HuffPost, November 29, 2011. Updated in December 06, 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/hartford-circus-fire_n_1117392

NBC Connecticut. “Remembering the 1944 Hartford Circus Fire.”, 1 July 2019, https://www.nbcconnecticut.com/news/local/HAR-Circus-Fire-Par allax-Remembering-the-1944-Hartford-Circus-Fire-511739861.html.

Woollett, Laura A. Big Top Burning: the Story of an Arsonist, a Missing Girl, and the Greatest Show on Earth, Chicago Review Press, 2015.

Special to The New York Times. “Youth Confess Fatal circus fire: Held for Arson.” New York Times, Jul 01, 1950, pp. 30.