Hartford Race Riots - By Jared Cyr

Hartford: A Hotbed of Racism

In the late 60's the city of Hartford becomes a hotbed of racial tension that leads to a series of riots over the years.

“No Danger of Race Riots in Hartford Police Officials Say.” It was August 4, 1919. Hartford’s black clergymen feared that the white mob violence raging through seven US cities could very well take place in their own city. Police chief Garrett J. Farrell tried to bolster the ministers by telling them that “there was no likelihood of a dispute between white and colored residents.” Reports of a racial incident on Windsor Street were probably “phoney,” Farrell said. While their prediction was correct for the time being, those tensions that caused worry would only worsen until the 1960s where it would bust wide open.” (Quote from Steve Thornton essay, “The Language of the Unheard: Racial Unrest in 20th-Century Hartford,” in the Connecituct History.org site)

Tension Builds

Throughout the United States during the 1960's, there were a variety of social movements occuring that would reach an apex during the decade. The urban riots of the ’60s illustrated the reality of race relations in America and the frustration of the reality Blacks in America were faced to endure. After experiencing extreme frustration over constant discrimination and segregation, the riots were their attempt to make their voices heard and initiate change. The frustration of Blacks across the country, including those in Hartford, passed the boiling point during 1967. The city of Hartford, Connecticut was a city that was much like the rest of the United States during the 60's, loaded with civil unrest that would build into tension that would be released through a series of riots in 1967 & 1969. Hartford faced stark dichotomy between the neighborhoods in the urban ghettos in the North End, which featured predominantly black, Puerto Rican, or impoverished citizens, and the white & middle class neighborhoods in the South End. During the first half of the 20th century, Hartford was home to some of the largest disparity between white & people of color in the country. According to a 1908 report black families lived in the “worst housing conditions in the country” (Thornton 2017). Child mortality was almost three times higher for black children than for whites,a 1923 Yale health study found. Tuberculosis deaths in blacks occurred with five times the frequency of whites during the 1930s. It wasn't the housing that was just terrible either, finding work was difficult due to a “practically universal prejudice” (Thornton 2017) against hiring black workers, as a government official told Connecticut business leaders in 1919. Five of the top Hartford factories employed no black men or women.

As the year pass, Hartford sees little change. Black activists, often backed by their churches & civil rights groups, led struggles in attempts to better their communities. Together, they created housing and other improvement projects. When they petitioned government for support, however, they often found themselves ignored. These reforms would be needed expotentially as from the 1950 to the 1960, Hartford saw a boom in its black population, seeing it more than double from 12,000 citizens in 1950 to over 25,000 in 1960. (Mostly due to false rumors of blacks being able to find work in the north) There was rapid change of population, in the Upper Albany area of Hartford, from white residents to Blacks occurred dramatically in 1965 when the Black population surged from 25% to 75% while white population decreased from 94% to 25%.” Blacks migrating to Hartford were segregated in the North End where they were subjected to overcrowded, substandard housing conditions.

On March 11, 1965, a determined group of local leaders met with Hartford’s commission on human relations in another attempt to call for urgent action. The NAACP, the Catholic Inter-racial Council, and the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) again laid out the problems facing the black community. A young group of upstarts, the North End Community Action Program (NECAP), was also in attendance. Both the public and private sectors received harsh criticism. “Negroes are being deprived of basic rights,” (Thornton 2017) said one leader, while others claimed that responses from city power brokers were “a whitewash” (Thornton 2017). The groups would however, leave frustrated and angry. “I hate to think of the demonstrations in Hartford we’re going to have if we don’t get some action,” said a representative of the Catholic group (Thornton 2017).

The stage has been set for a series of riots...

1967 Riot

Hartford 1967 Riot

Civil unrest sparks into a riot

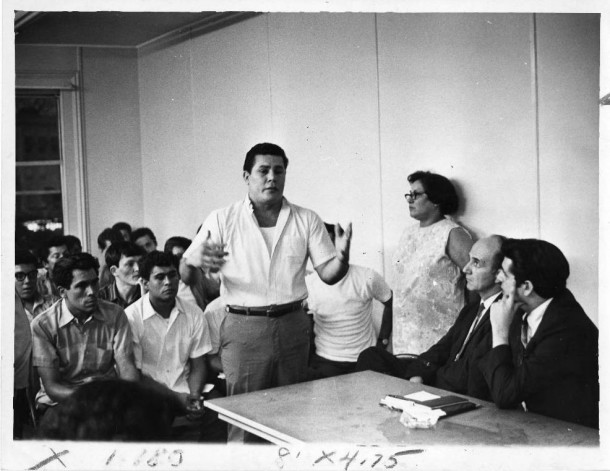

On July 12, 1967 a black teenager was arrested for allegedly swearing at a waitress (Thornton 2017). Two days later, on Thursday July 14, 1967 a group of young men from the North End spoke to officials to determine the causes of the disorders occurring in the ghetto throughout July, citing the arrest from two days earlier as an example. The young men, in their late teens and early twenties reported to officials the causes of the disorders and suggested possible solutions in slowing down the disturbances. One of the complaints from the Blacks concerned unemployment in the North End businesses, which were owned and run by white Americans. Not only did the white owners not employ Blacks, but they raised the prices of merchandise in these stores. Hartford Mayor George Kinsella, said that he would work with Governor Dempsey and the state labor commissioner to address this problem.

Tensions would cool for several weeks, but the goals to improve the conditions in the ghettos of the North End, mainly between the citizens of color, and the police & white business owners did not see any improvement. Hartford would see 4 consecutive nights of rioting, starting on September 18, 1967. Police would end up resorting to using tear gas to disperse crowds of rioting youth in the streets. Although the tear gas would disperse the crowds, the teens would regroup on a different street. Street hopping became a pattern of rioting in Hartford. Although Mayor Kinsella had originally characterized the youth counter-rioters in July as “dedicated, nice young men,” those youth Kinsella encountered on the streets in the aftermath of the September riots were reclassified as “hoodlums” and Kinsella stated, “I don’t know why those kids are doing it.” Police Chief Kerrigan stated that these disorders would not be tolerated. “We will continue to break up any gangs that are formed and we will move rapidly to restore law and order.” The Black Caucus, a new group of counter-rioters, came forward to state that “violence was inevitable and grew out of white harassment and frustration suffered over the years by minority groups."

The Black Caucus served not only as a negotiation team for North End residents, but also led peaceful demonstrations as an alternative (and essential leader) to the violence occurring in the North End. Although the first few marches were stopped by police, the Black Caucus made successful marches through downtown and to the South end. A peaceful pray-in was conducted at Constitution Plaza. A triumphant march to the South End symbolized Hartford’s Black population’s refusal to remain segregated in the North End of the city. Although the disturbances of 1967 had finally cooled off, Hartford’s turbulence was not over. Police brutality comntinued and served as the impetus for the riots in 1969.

Hartford Riots of 1969

Tempers flair and explode as Hartford is rocked by a series of riots during the summer of 1969

June 1969 Riots

Hartford would face several riots during the summer of 1969. Just like the riot of 1967, it wasn't one direct incident but several forces coming together, needing only but an incident to spark anger over the resentment these communities felt into full blown violence. This time, it wouldn't just be the black citizens of Hartford taking part, but the Puerto Rican citizens as well.

The first of these riots began on June 5 and would last several nights until June 7. In an attempt to restore peace, Mayor Uccello issued a city wide curfew and imposed a state of emergency on Friday, June 6. The announcement of the curlew was broadcast over television and radio in multiple languages: Spanish, French, Polish, Italian, and English. Additionally, sound trucks made the curfew announcement in neighborhoods in Spanish and English. The community and national leaders endorsed the curfew as they drafted and circulated a flyer urging other community residents to abide by the curfew. This flyer was signed by NAACP, the Tenant Relations Division of the Hartford Housing Authority, Neighborhood Service Centers, Catholic Interracial Council, Community Renewal Team, High Noon, Black Democratic Caucus, and the Blue Hills Civic Association. But why then and what caused the riot?

The Puerto Rican community took center stage during the June 1969 riots as they responded to what they had felt were increasing tensions between them and the Hartford police force. They felt they were the target of a series of unlawful arrest, and felt even more assured in their assumptions as over the next several nights they were unfairly targeted & attacked by the police. The curfew continued for a second night on Saturday, June 7. During this second night, many more arrests were made for cutiew violation. In spite of numerous arrests, the city manager declared that the curfew was a success, however, the cufiew would be cancelled for the third night. Most witnesses noticed that residents were reluctant to obey the curfew on the second evening, hence the increased arrests. Although the cur-hew was over, the state of emergency remained in effect on Sunday. By the end of the weekend, tensions had cooled, but the violence wouldn't over for the summer.

Comanchero Riots

The disturbances returned in August 1969. On Sunday, August 10, riots were sparked by rumors that the Comancheros, a white motorcycle gang, had assaulted an elderly Puerto Rican on the South Green. Hostility already existed between Puerto Ricans & the Comancheros as the motorcycle gang had been bullying the Puerto Ricans who, in response, would throw bricks back upon the crowds, refused to obey orders to disperse the crowds, and formally filed a complaint against the brutality. As the violence broke out and the police responded, the Puerto Rican community believed they again were the target of unjust police discipline. On August 19, after 53 arrests on Puerto Ricans were made during the previous week, the PR community gathered in a church to issue complaints of police cruelty. Arthur Johnson, Director of the Human Relations Commission, quickly became aware that many individuals issuing complaints had already filed charges, of which no action had been taken. To further their anger, the Hartford Police had made a statement that two of the only four Spanish speaking officers, Jose Garay and Jose Rivera would be facing disciplinary action for refusing to obey orders. City Manager Freedman had also announced he would launch a full investigation into the current uprisings. But while this placated Puerto Ricans for the time being, no investigation would took place. The lack of the investigation again illustrates the lack of commitment by city officials to improve the poverty-stricken areas of the city and to improve race relations. The riots would again last several days and nights, coming to an end on August 13th with some additional isolated violence on the 15th as well. But again, this still wasn't the end of the riots Hartford would deal with in 1969.

Riots of Sept. '69

September Riots of '69

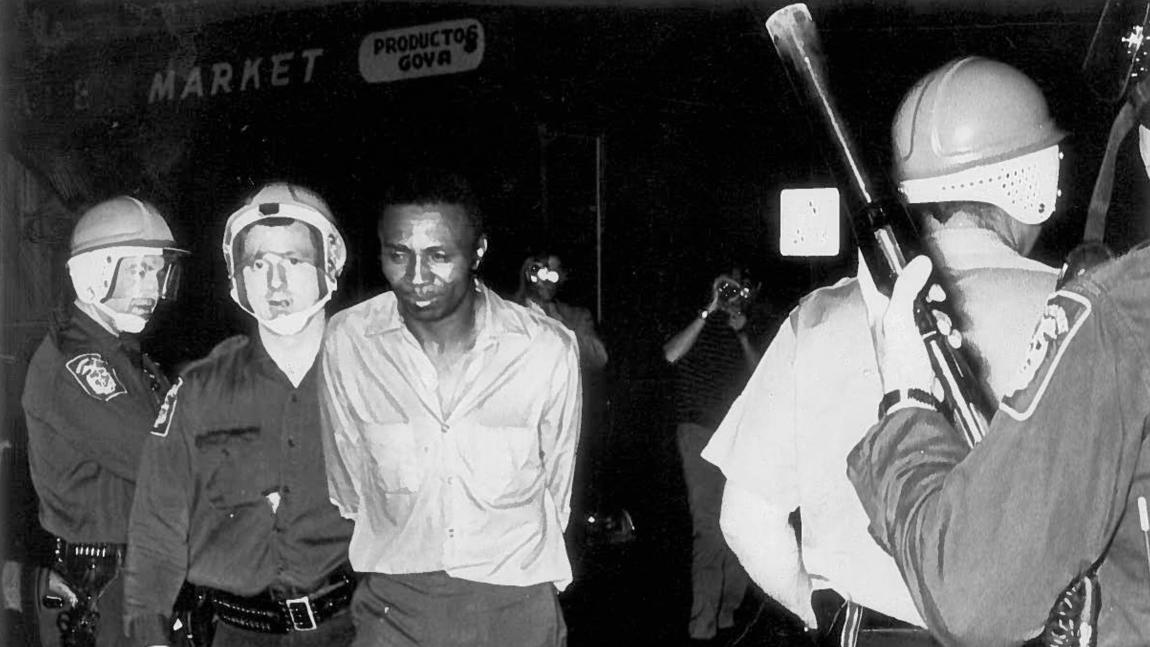

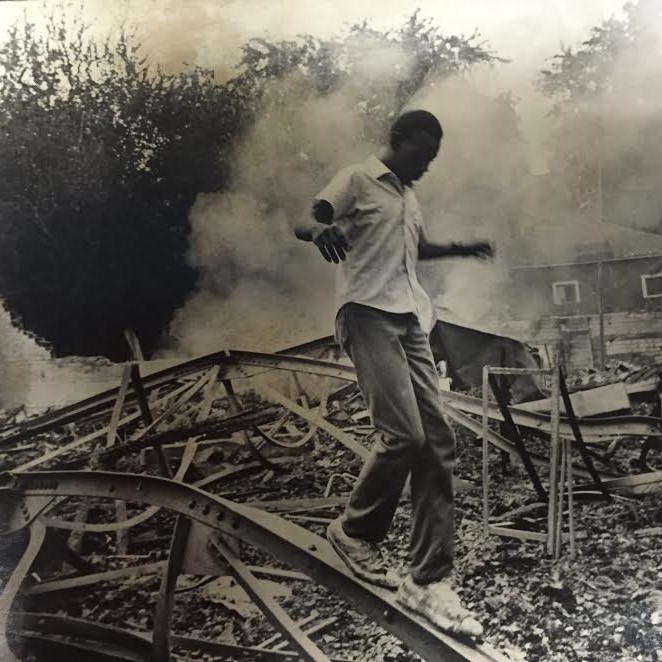

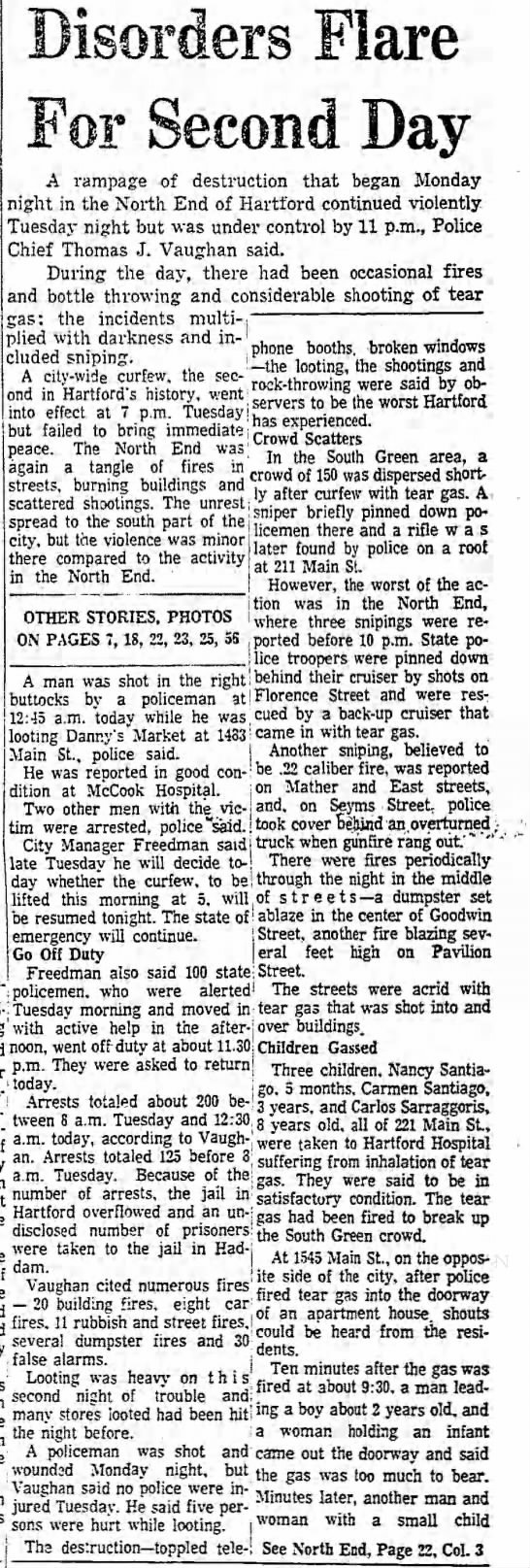

The most destructive of the riots Hartford would face started up on September 1st. The black community joined in the civil unrest with the Puerto Ricans when a 16 year old black teen, Dennis Jones, was shot and killed by a West Hartford police officer on August 29. Chaos ensued. The North End was destroyed as fires were ablaze, buildings looted, and shots fired in the North End. Between 8 a.m. on Tuesday and 12:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 50 people had been injured and 50 fires were set. By 8 a.m, on Wednesday, the number of people arrested had climbed to 266. By Friday, September 5, arrests had reached 500 and the Hartford jail could no longer handle these numbers. The jail in Haddam was used for the overflow. Many stores were looted several times over the first two days of riots. One liquor store was wiped clean of all alcohol and reports of snipers occurred for the first time, It was not until Monday, September 8 that Mayor Uccello lifted the state of emergency.

African American leaders in Hartford denounced the violence but cautioned city officials to look for solutions to avoid future unrest. One NAACP leader stated:

The violence and lawlessness is due to the reprehensible behavior of a small number of blacks and Puerto Rican citizens... The NAACP deplores and condemns these actions.

While it was acknowledged that only a few were responsible, cityo fficials generalized all Puerto Ricans as being responsible for the disorders and issued “blanket indictments” against African Americans and Puerto Ricans. Mayor Uccello called them "hoodlums... who would steal no matter what the social conditions." City Councilman Collin Bennett correctly assessed the situation as he stated:

"[the] riot was evidence of ‘poor relationships and lack of communication between the city government and members of the Spanish-speaking community. This segment of our society feels that there is no one to represent their interests in city hall, and this has been partly responsible for the increased tension.. ."

Despite this insight by Councilman Bennett, other city officials would continue to turn a blind eye to the discrimination occurring within the city. The events of 1969 launched Puerto Ricans into politics. However, communication lines between North End residents and city officials continued to remain weak. Mayor Uccello maintained a hard line regarding the situation and those involved. She stated:

The damage is considerably more than in June.. .we are prepared, should it take a turn for the worse, to meet the situation with state police, national guard, or any necessary fore. I do not want to rush terminating the state of emergency. I will not cut the cur-hew until I feel confident that the situation is completely under control. I want people to know we are not going to stand for this kind of violence.

After a calm had been reached, both black citizens and Puerto Rican citizens expressed their anger over the racism in Hartford as one remarked, “Americans called us pigs so we started throwing garbage. This statement is very indicative of how little change was made since 1967 and the continuation of troubled race relations occurring in Hartford, and throughout the nation. Similar to Hartford, nationally, conditions in American cities remained unchanged. The Kerner commission distributed surveys in order to form an opinion about conditions in urban cities since the disorders subsided. The most common reaction was “nothing much changed. Employment, or lack thereof, remained the same. Disorder continued throughout the summer in most cities. The commission report, “In several cities, the principal official response was to train and equip the police and auxiliary law emorcement agencies with more sophisticated weapons.“ However, this solution did not resolve the precipitating cause of the disorders.The Kemer Commission reported:

Virtually every major episode of urban violence in the summer of 1967 was foreshadowed by an accumulation of unresolved grievance by ghetto residents against local authorities.. .Coinciding with this high dissatisfaction, confidence in the willingness and ability of local government officials to respond to Negro grievances was low.

The Kemer Commission reached the conclusion that the problem of urban America was based in the ghettos, specifically blaming the lack of communication between the residents and city officials. The commission reported:

The racial disorder of last summer in part reflects the failure of all levels of government - federal and state as well as local - to come to grips with the problems of our cities. The ghetto symbolizes the dilemma: a widening gap between human needs and public resources and a growing cynicism regarding the commitment of community institutions and leadership to meet these needs.

Cynicism was alive in Hartford as North End residents continued to face discrimination and Hartford city officials continued to make empty promises.

Sources:

- "Hartford, Connecticut Riot (1969)" by: Maritza Fernandez. Posted in Black Past on March 1, 2018. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hartford-connecticut-riot-1969/

- The Language of the Unheard: Racial Unrest in 20th-Century Hartford" by Steve Thornton. Posted in Connecticut History.org, February 13, 2017, https://connecticuthistory.org/the-language-of-the-unheard-racial-unrest-in-20th-century-hartford/

- "An Interactive Map of Latino Urban Riots and Social Unrest" by Aaron G. Fountain, Jr. Jul 12, 2016 in Latino Rebels, https://www.latinorebels.com/2016/07/12/a-visual-map-of-latino-urban-riots-and-social-unrest/

- "The Late 1960s: Unrest In Hartford", Gallery of Photos from the Hartford Courant (2014), https://www.courant.com/courant-250/moments-in-history/hc-reactions-to-martin-luther-king-jrs-death-20140521-photogallery.html

- "Maria Sánchez, State Representative and Community Advocate" posted in Connecituct History.org (January 3, 2017), https://connecticuthistory.org/maria-sanchez-state-representative-and-community-advocate/

Newspapers clip images:

- 1967 Hartford Riots, Clipped from The Bridgeport Post, 20 Sep 1967, Wed, Page 1, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7024339/1967_hartford_riots/

- 1969 Hartford Riots, Clipped from Hartford Courant, 03 Sep 1969, Wed, Page 1, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/10091100/1969_hartford_riots/

Pingback: This #thread is for those of you struggling to comprehend that the recent murders are just a fraction of racial violence in the United States. We are protesting for #GeorgeFloyd #BreonnaTaylor, #AhmaudArbery AND hundreds of years of oppression.