1854 Boiling Over

By: Mary Mahoney, PhD

1854: Boiling Over

In the early afternoon of Thursday, March 2, 1854, a Mr. Ashe, the head painter of the Fales & Gray Car Factory, was standing on the bank of the Little River, south of the factory located on Potter Street. Gazing back on the factory, Ashe attempted to commit to canvas a landscape that could be replicated on the railway cars produced by his employer. What he saw next defied any attempt at illustration.

Just as he started to sketch, he later remembered, a "shock came, and the building trembled before him, then fell with an awful crash." Terrified, Ashe never completed the sketch. Although he was a talented artist, he could "hardly impress upon canvas the vivid imagery or terrible reality rather, that burst out before him in that shock of destruction and death.” What Mr. Ashe saw was the explosion of the Fales & Gray factory, which killed nineteen of the company's three -hundred workers instantly and severely wounded twenty-three others. Every building on the property was “shivered to atoms” and pieces of the factory’s steam boiler were found as far afield as two-hundred feet away. Indeed, Mr. Ashe, or any artist for that matter, might have felt unequipped to represent the scene. Instead, the city’s worst disaster in almost 100 years was etched into memory using photography. The resulting photographs, believed to be some of the first photographs ever taken of Hartford, show the remains of the factory and focus on the devastation of Potter Street.

Terrible as the physical devastation was, public remarks spawned by the explosion printed in newspapers and preached from pulpits quickly moved beyond the physical destruction of the factory site. Who was at fault for the explosion? How should the city respond? Most importantly for some, what might all of this suffering mean? These were the questions that haunted Hartford in the days following the blast. Check out the following pages to explore the many different ways that people answered these questions and the ways in which people coped with the disaster.

An Explosion

While seemingly every facet of the explosion would be disputed after the fact, no one could dispute that around 2 pm on March 2nd, the steam boiler in the main building of the Fales & Gray car factory exploded, demolishing the buildings that made up the factory complex. How can we know what happened that day in 1854? We can only rely on what our sources say, and attempt to understand what people in Hartford thought was happening on their terms. To do this, we have to turn to what sources have survived.

One of the main sources we have is a pamphlet entitled “An Account of the Terrible Explosion at Fales & Gray’s Car Manufactory” which was published soon after the tragedy for the benefit of the survivors. It includes a transcript of the inquest, and of some of the sermons that focused on the blast. For our purposes, let’s take a look at the introductory section that described the event itself. The anonymous authors of this account focus less on the mechanics of the boiler and what might have caused the blast, then on appeals to emotion to instill in the reader the devastation of the aftermath. Here is their description of moments after the explosion:

“To paint the agony of the relatives, wives, children, mothers and fathers, whose relatives were sufferers, would be impossible. They rushed wildly to and fro, while the workmen were extricating the sufferers, calling upon their relatives in the most piteous tones; and when a body was brought out, the eagerness they manifested to know if it was that of a relative, must be imagined, for no words can describe. Suffice it to say, that in many instances, they failed to recognize their own relatives, so blackened, and distorted, and mutilated were the bodies, by the dirt, bruises, and fearful scalds. Some were so badly scalded, that on touching them the skin peeled off in the hand. Many of the dead were only recognized by the clothing they wore, and as their relatives sought them out, and found them in the arms of death, the scenes which ensued on recognition were painful in the extreme. The majority of the workmen lived in the immediate neighborhood, consequently the interest excited by the catastrophe, brought large troops of friends and acquaintances to the spot, many of whom, especially the ladies, exerted themselves to soothe the wild grief of the bereaved.”

How does this passage help us to understand the explosion and its aftermath? While we can never know exactly what happened on this tragic day, this anonymous account invites our imaginations to picture a chaotic scene that involved not only the destroyed factory, but the surrounding neighborhood where many of the workers lived. Some of the addresses of the dead were listed in the pamphlet, showing readers how closely connected the surrounding neighborhoods were to the factory. Women rushed to the scene to help the grieving, and to help identify the dead and wounded who were made unrecognizable to their own families by the blast. The purpose of the pamphlet was not only to present a narrative of the explosion, but to produce sympathy in the reader, and encourage further donations to the surviving families.

The Victims

Beyond the cost of the explosion for the mother of Daniel and Samuel Camp and their families, this account also shows us how Hartford residents dealt with the aftermath of the blast in terms of the dead and wounded. Daniel S. Camp was taken home to die, and his brother’s body was also returned home. The pamphlet lists the addresses of some of the dead and wounded, but the addresses of many of the wounded remained unknown. Where were they taken to receive medical care?

In the aftermath of the 1766 explosion, many of the wounded were taken to surrounding homes and stayed there until they were well enough to return home. This was when Hartford was a relatively small community made up of family networks that were largely interconnected. There were few strangers in Hartford in 1766. The same could not be said for Hartford in 1854.

With the rise of industry, many immigrants and others made Hartford their homes to find work. Who would care for these strangers? This was a concern that the city would have to address in light of the 1854 disaster. Before they could put forward with suggestions for how to prevent a similar tragedy, however, the city had to solve the mystery of who was to blame for the Fales & Gray Car Factory explosion.

Finding Fault

A jury composed of the city’s elite men convened the day after the explosion to interview witnesses and assign blame for the disaster. Dressed in top hats and overcoats, this jury toured the wreckage, picking apart debris littered with the chilling remains of the day. Afterwards, they travelled around the city interviewing witnesses, some of whom lay dying or recuperating in their beds. Readers of the Hartford Daily Courant and Hartford Times could follow along on the front pages of their newspapers as full transcripts of the inquest were printed in each new edition for the length of the six -day investigation.

The case hinged on whether or not the engineer in charge of the steam boiler, John McCune, had been “careless” in his duties. Some accused him of neglecting the boiler until the water levels fell too low, causing the blast. The boiler in question had been replaced a month before. Was the boiler itself faulty? Was McCune being asked to do too much by his employers who would not grant him an assistant as he requested? Was McCune drunk on the job? These were all questions posed to witnesses. The entirety of the inquest was reprinted in the pamphlet later sold to benefit victims.

Assigning Blame

When the interviews were complete, the inquest ruled that the blast was likely due to the presence of too much steam in the boiler, implicating the engineer John McCune for negligence. They recommended that the city monitor boilers throughout the city through some system of inspection, and recommended that engineers not be hired without the proper training.

It would take a decade before this kind of regulation was made into law in Hartford. While the city leaders may have felt some resolution in creating an official explanation for the tragedy’s cause, the city’s spiritual leaders made it their mission to understand the tragedy in a spiritual context.

How could anyone make sense of the seemingly meaningless loss of human life?

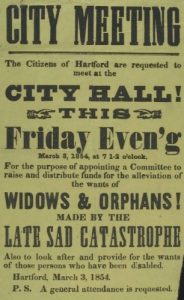

Valuing Lives, Compensating Victims

The night after the explosion, a group of Hartford residents met to establish to a fund to benefit the wounded and the families of the dead. A 50- page pamphlet including a description of the explosion, a transcript of the inquest and a selection of sermons was put together and sold in an edition of 1000 at a price of 25 cents to benefit the fund. The Hartford Daily Courant reported on large donations that came in from various donors out of state, as well as from prominent local businessmen such as Samuel Colt, who donated over $500 along with his workers.

But how would the fund be dispensed? Would the families of the dead receive more than the wounded? Of the wounded, would a disabled hand be valued more highly than a foot? How would such determinations be made? We can begin to answer this question by looking at the account book of how the funds were distributed. It would appear that the money was divided not by degree of injury, but by the stature of the injured.

What Did the People Have to Say About the Explosion?

Finding Comfort in the "Valley of Affliction"

Hartford residents may have sought solace in the city’s churches to come to grips with the tragedy that rocked their community. Three of these sermons made their way into print, and reflect the differing visions of how the tragedy might be interpreted as both a sign of God’s will and a lesson for the living.

Rev. Thomas M. Clark, the minister of Christ Church, preached on Samuel XX. 3: “There is but a step between me and death.” He recalled the 1766 schoolhouse explosion, and noted how much the world had changed since then. The new technologies that caused the terrible explosion that had also taken several lives would have been entirely foreign to the Hartford residents of 1766. Like the official inquest, he did not blame the owners of the factory, but again turned to the carelessness of the engineer John McCune.

“Of course there is no criminal intent, no expectation of calamity,” Clark reasoned discussing McCune, “the official is merely careless for a moment, and in that moment, his own life and the lives of others are sacrificed, and years of agony are entailed upon society.” The only meaning he could find in this suffering was the capacity of the tragedy to strengthen the souls of the survivors, saying, “The spiritual fiber of the soul is often strengthened more in an hour of intense suffering, than it is by years of ordinary life.” Another lesson, he intoned, was the way in which the blast could bind together “the discordant family of man.” The days following the explosion were a time for the city to come together as a community, even using the language of family to imagine this bond. “We are drawn very near to each other,” he reminded those listening in the church pews and reading his words in the columns of the Hartford Courant, “when we meet in the valley of affliction.”

“To Startle the World”: A Different Understanding of Tragedy

The Reverend Walter Clarke found few signs for hope in the days following the explosion. The other Reverend Clark may have looked for community unity after the blast, but the only unifying factor Rev. Walter Clarke saw in Hartford in the sad days of March, 1854 was the residents’ capacity for sin. “I simply say,” he warned, “that calamities come to this world because sin is here, and that they come to startle the world, and to remind the wicked that there is sin among us.” For Clarke, the blast was a reflection not just on the sinfulness of the 19 men who lost their lives, but on all sinners in Hartford who should take heed. Clarke invited his listeners to listen to the crumbled remains of the factory as they spoke to the city residents on their sinfulness:

Calamity is speaking to-day in our ears. Every splinter and fragment and fallen brick of yonder awful wreck; every forsaken forge, and every blood-stained tool, moans in our hearing its message from God. Surviving sinners of Hartford! The wreck, the dead, the elements around you, are speaking to you. And their message is, Except ye repent, ye shall all perish likewise. Let it be heard through all your factories and in all your dwellings; let it be echoed over every bench and engine, and anvil, upon every street and at every corner; around the graves of the dead, and at the tables of the living; wherever you go wherever you gather, whatever you do, let it haunt you in every place, let it come to you in your dreams, let it find you in your revels. Sabbath-days and week-days, let it ring in every ear and thunder in every conscience. Except ye repent, ye living men – except ye repent, ye shall perish also.

“The Reckless Spirit of Enterprise”: A Third Lesson on Tragedy

In the search for meaning after the tragedy, Rev. Frederic Hinckley at the Unitarian Church of the Saviour preached not on the tragedy as a sign of man’s sinfulness, but linked the explosion to the dangers of man’s reliance on enterprise. Why did so many men die needlessly on Potter Street? According to Hinckley, they were “sacrificed.” “Yes,” he elaborated, “sacrificed to the reckless spirit of enterprise of this mid-century; uselessly, murderously destroyed that more physical power might be obtained, more speed secured, more work performed, and greater material results produced.”

He delighted in the power of steam to increase the speed and reach of travel and to bolster industry and the production of goods, but worried about the human cost. Steam was a power that humans still did not fully understand, and men in business would do well to be cautious of its use and the dangers it posed. It was foolish, he argued, for factory owners to house a boiler in the center of the factory where its explosion could kill so many. Further, no man should be allowed to engineer steam power for a factory without the upmost training. More attention should be placed on the human price of labor, and not the material gains of frenzied production. “In our demands upon travel or labor,” Hinckley noted of the use of steam power, “. . . we prefer safety to speed, and value human life above material power.”

The foundation for Hartford Hospital is set

Preparing for the Future, or Hartford Gets a Hospital

Another major initiative following the explosion that was meant to help the city prepare for any further disasters was the founding of Hartford Hospital. In both the Schoolhouse explosion of 1766 and the factory explosion of 1854, the wounded healed at home, or in the homes of acquaintances that lived near the site of the blasts. This became increasingly difficult, however, with the changing scale of the population. Now with a population of 15,000, the city had grown much bigger than the initial community of families that populated Hartford in 1766. Immigrants and workers from other states made Hartford their home as they sought work in the city’s factories and businesses.

Who was responsible for caring for these “strangers?” Driven by a spirit of benevolence, the city’s leaders believed the hospital would care for the city’s residents. As Dr. George Hawley noted at the hospital’s dedication in 1859, the Hospital would serve as “an asylum for the disabled and destitute.” Those with enough resources to be treated at home continued to prefer private care, but for those without that option, the hospital now served as a refuge.

The original buildings of Hartford Hospital, in an undated postcard.

The city had no public hospital when a steam boiler at the Fales and Gray Car Works exploded on March 2, 1854. Nine people died immediately; 12 more died later; 50 were injured. What happened next was civic action at its best. "Hartford's citizenry was appalled at the city's inadequate facilities for caring for a large number of injured people," according to historian Glenn Weaver. "Two months to the day after the explosion, a public meeting voted in favor of a public hospital, and before the end of the month the Hartford Hospital was organized." (Quoted from "Hartford: An Illustrated History of Connecticut's Capital.")

Pingback: March 2: A Deadly Accident Leads to Hartford’s First Hospital – Today in Connecticut History