The Story of the I-84 Interchange in Hartford

By: Evan Metzner

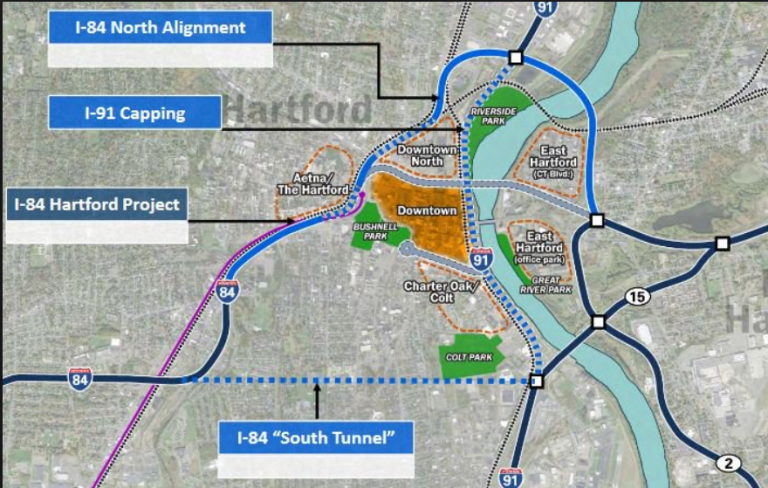

Hartford is a city dominated by highways. Two major thoroughfares, I-84 and I-91, run right through the center of the city, commanding attention from pedestrians and drivers alike. These highways are heavily trafficked, handling a vast array of local, regional, and commuter traffic complex enough to make any transportation planners head spin. And spin they have. Hartford’s traffic woes, lead by ever increasing delays and congestion on the highways, have only grown worse over time. While it is rare to find a city happy with its traffic, Hartford is in rarefied air, ranking as the fifth most congested medium-sized city in the country in a 2015 study. That said, traffic backup is not the only legacy of the interstates. The placement of the highways through the center of Hartford has had a significant impact on the development of the city, bifurcating neighborhoods, inhibiting development, and restricting access to potentially valuable riverfront land in the center of the city. Given these negative outcomes, why then were the freeways built so centrally? The answer is surprisingly dramatic, involving the arrival of a foreign power broker of unrivaled influence, an influence-peddling drama played out at the pinnacle of Hartford high society, and a controversial new image of one of Hartford’s favorite daughters.

The Beginnings

Lying in the heart of Connecticut, centrally located between the national hubs of New York and Boston, Hartford has a long history as a regional transportation hub and central administrative district. Having been a co-capital of the state with New Haven since 1701, Hartford wasn’t named the primary capital until 1875. Importantly, this occurred only three years after the establishment of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad in 1872, which put Hartford at the center of a consolidated rail system stretching from New York City to Springfield Massachusetts, and Boston by extension.

Hartford’s role as a transportation hub would only increase after the 1956 Federal Aid Highway Act was passed, facilitating the creation and formal establishment of I-91 and I-84 in the Hartford area. I-91 was based on existing infrastructure, stringing together already heavily used main roads into one singular interstate. I-84 was very different, built mainly from scratch. It changed between proposed routes several times before settling on its current path, only shifting to terminate in central Massachusetts after Rhode Island canceled a planned eastern extension to Providence for environmental reasons in 1983. This fluidity throughout the construction process is indicative of the freedom that the designers of I-84 had relative to most major highways, which often had to connect older segments of main roads and were constrained by the locations of these older segments.

The Interchange

The relative freedom of the transportation planners who created I-84 makes the location and of the I-84 interchange all the more puzzling. Without existing infrastructure forcing I-84 to merge in that spot, it makes little sense to put such a major interchange with multiple complex entry and exit ramps in such a densely populated and central area. Joel Lang, writing for the Hartford Courant in 1983, even quoted the director of the highway program for the Center for Auto Safety, who called I-84 in Hartford “one of the most disgraceful pieces of highway ever built… The ramps are completely and utterly misplaced, wrongly designed and inadequate…”. This damning indictment of the I-84 interchange has proved prescient, as the interchange has been found to be one of the primary drivers of traffic in modern-day Hartford. The city government has gone so far as to fund a feasibility study for enhancing or replacing the existing interchange, even in the face of major budget issues. If the interchange was moved out of the center of downtown or the entry and exit ramps were laid out more logically, there could be an enormous positive effect on traffic flow, economic activity, and property value. All these factors paint the freeway construction of I-84 as one of the biggest mistakes in the creation of modern Hartford. However, it is likely that the structure of the interchange was no mere mistake, rather a politically motivated misstep by a historic Hartford institution.

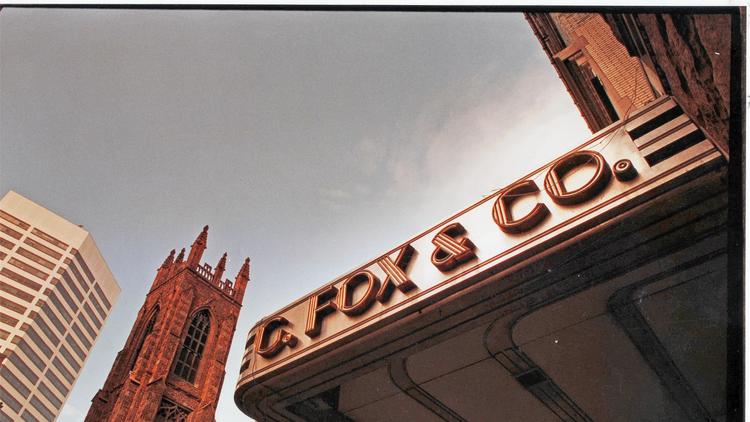

There has long been speculation that Beatrice Fox Auerbach, wealthy owner of the G Fox & Co department store in the late 20th century, used her political clout to influence the construction of the interchange to create a layout in which the exit ramps would lead directly to parking for her department store. She did have the influence to do so. Auerbach was a bishop in the community, widely respected by community leaders and citizens alike. More than that, the G Fox department store was a fixture of the community. Described as “a department store of such vastness and splendor that women shoppers would don their Sunday-best hats and gloves for the occasion”, G Fox & Co. attracted people from all over Connecticut and western Massachusetts. It was an institution. It put Hartford on the map.

Further damning testimony is provided by Arthur Lumsden, the president of the Greater Hartford Chamber of Commerce at the time of the highway’s construction, seemed to corroborate this suspicion. In a 1983 Hartford Courant article, Lumsden is quoted asserting that “Mrs. Auerbach and Judge [Solomon] Elsner [Auerbach’s lawyer], they kind of designed the East-West Expressway to come into G. Fox”. While unable to influence highway placement on a regional level, that was left to the US army corps of engineers, the state and Auerbach would have had complete freedom with the placement of entrance and exit ramps. With the introduction of this ulterior motive, the logic behind the seemingly arbitrary or negligent ramp construction begins to reveal itself, and one of the “most disgraceful pieces of highway ever built” begins to make sense.

The Fox

Given the poor long-term outcomes of this construction, the imposition of this poorly optimized infrastructure may seem like an act of pure selfishness on the part of Auerbach and the city council; however, all that knew Auerbach in any capacity have voiced disbelief when confronted with this theory. They cite her great philanthropic work, as well as her famously mild manner and love for the city as evidence of the implausibility of this claim. Auerbach’s granddaughter echoed this sentiment in a 2007 interview, stating it would have been “very much out of character” for her grandmother to use her political clout for her own financial benefit.

I am inclined to believe this sentiment. Auerbach was a great philanthropist, starting the Beatrice Fox Auerbach Foundation that is still active to this day. She was loved by her employees, offering great pay and hours as well as innovative benefit packages like scholarships for the children of employees. She is even notorious for knowing “all of her employees – and their children – by name”. All of this evidenced by her fantastic funeral, the largest ever for a private citizen in Hartford. It seems unlikely that such a fixture of the community would knowingly hobble infrastructure so vital to the community she always strove to improve for any reason. An alternate explanation is needed.

“If she pressed for something, it would be something that she thought was a social inequity or something like that. But she would not misuse her power” – Rena Koopman (Auerbach’s Granddaughter)

The Greater Good

The truth, as it often does, requires more context. In the late 60’s and early 70’s, Hartford was beginning the long, painful transition from a wealthy commercial and industrial hub to a faltering post-industrial city. As in many other former industrial cities, this transition precipitated a mass exodus of people and wealth from the inner city to the suburbs, often referred to as white flight. Hartford had been known for its great urban department stores, with people coming in from all around the state to shop in its urban center. However, by the time the I-84 interchange was being put in, only the G Fox department store remained. A fixture of the community and a relic of the past, all wrapped up in one gilded package. All the other grand shopping centers of Hartford’s past had fled to the suburbs in search of lower rents or been pushed out of business. It’s fair to say that if G Fox & Co was lost too, Hartford’s already struggling downtown community would have taken a punishing hit, pushing even more people out to the suburbs.

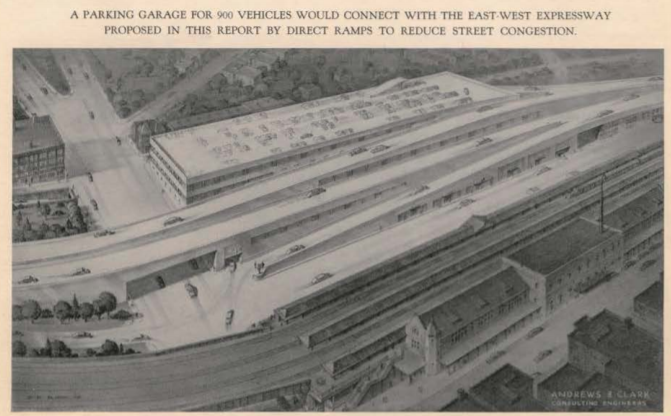

Ironically, one of the primary causes of this exodus was the automobile itself. Increased transportation range and comfort paired with decreasing costs was allowing people to forgo traditional modes of urban transport such as trains, streetcars, and walking; giving them the freedom to access shopping centers located further outside the city that would otherwise have been inaccessible. At the same time, increased automobile traffic caused by this shift away from public transport was making getting to and parking at downtown department stores a serious trial for shoppers and residents alike. This last point is important. It wasn’t the G Fox department store itself to which the mess of exit ramps funneled drivers, rather the $50 million Dollar parking garage built next to the store. The funneling of traffic here would have helped G Fox and Co, but it would also provide easy direct access to readily available parking for out of town visitors; potentially reducing congestion on surrounding streets and helping to re-establish Hartford as a commercial hub. If traffic was the problem, this interchange was meant to be the solution.

Doctors, we are told, bury their mistakes, planners by the same token embalm theirs, and engineers inflict them on their children’s children. Of these three types of error, the engineering variety is in the long run the most costly to the community.– Robert Moses

The argument here is that Auerbach’s intervention was simply another act of philanthropy. Lynne Lumsden, Arthur Lumsden’s daughter and reporter at the Hartford News, echoes this. As Kathleen Mcwilliams of the Hartford Courant writes, “Lumsden asserts that Auerbach didn’t misuse her power at all, but rather that she effectively harnessed it to serve the greater good — easing downtown traffic woes and helping all the downtown businesses.” Lumsden went on to explain the project was meant to be “good for the whole community downtown. It wasn’t just a selfish motivation. It wasn’t just greed that would motivate those decisions, it was social consciousness”.

While the true motivation behind the construction of the now infamous interchange may be lost to time, the infrastructure itself is a powerful reminder that the things we create can and will outlast us. And if we’re not careful, over time they can come to define us, for better or worse.