Individual Naturalization

At the present time there are in Porto Rico

a good many Porto Ricans who are citizens

of the United States. They have become so

by moving over to the mainland and getting

naturalized and going back. There are also

a good many Americans who moved down

there who are citizens of America, and in

addition to these citizens there are the general

mass of Porto Rican people who are not

practically citizens of the United States, but

who are members of the people of Porto Rico.

I do not see that the situation that this bill

proposes introduces any novel principle

any different from what now exists.

Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War,

Hearings for H.R. 20048 (1912)

In his memoirs, Bernardo Vega recounts how sometime in 1916 he enrolled in a local public school in New York city and tried to argue with his teacher that his Puerto Rican citizenship barred him from acquiring a naturalized citizenship. One night, the teacher talked about the naturalization process in the U.S. and explained that immigrants were required to renounce their loyalty to a sovereign or citizenship in order to begin the naturalization process. Vega argued that unlike his Hungarian and German classmates, Puerto Rican citizens were unable to comply with this requirement and were therefore unable to naturalize. As Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson’s comments suggest, Bernardo Vega was wrong.

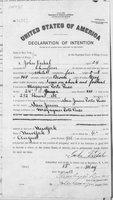

Between the ratification of the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and the enactment of the Jones Act of 1917, Congress applied and enacted three laws that enabled individual Puerto Ricans to acquire a U.S. citizenship via individual naturalization. Puerto Rican women who married U.S. citizens acquired their spouses’ citizenship under the terms of the prevailing doctrine of coverture. In addition, in 1906 Congress began enacting immigration and naturalization laws with special provisions enabling Puerto Ricans to undergo the prevailing naturalization process in a state or incorporated territory. Suffice it to say that individual Puerto Rican citizens were able to acquire a U.S. citizenship prior to the enactment of the Jones Act of 1917 through various naturalization laws.

The U.S. doctrine of coverture established that marriage was a voluntary form or process of naturalization. Women automatically, and without a choice, acquired the citizenship of their male spouse. Although Spanish law also provided for coverture, the U.S. doctrine of coverture was applied to Puerto Rico in two ways following the enactment of the Foraker Act. Section 14 of the Foraker Act established that the statutory laws of the United States not locally inapplicable would have the same force and effect in Puerto Rico as in the United States. This provision extended the U.S. interpretation of the doctrine of coverture to Puerto Rico. The local U.S. District Court for Puerto Rico also applied this doctrine through jurisprudence in cases such as Dastas Garrosi v. Garrosi (1904), Martínez de Hernández v. Casañas (1907), and Echcandia v. San Sebastián (1909). The U.S. doctrine of coverture remained in force in Puerto Rico until 1934, when Congress amended the Jones Act of 1917 and extended the Cable Act of 1922 to Puerto Rico.

In 1906 Congress enacted the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization Act (BINA) enabling individuals born in Puerto Rico and the other insular territories to undergo the prevailing naturalization process and acquire a U.S. citizenship. Section 30 established:

That all the applicable provisions of the naturalization laws of the United States shall apply to and be held to authorize admission to citizenship of all persons not citizens who owe permanent allegiance to the United States, and who may become residents of any State or organized Territory of the United States, with the following modifications: The applicant shall not be required to renounce allegiance to any foreign sovereignty; he shall make his declaration of intention to become a citizen of the United States at least two years prior to his admission; and residence within the jurisdiction of the United States, owing such permanent allegiance, shall be regarded as residence within the United States within the meaning of the five years' residence clause of the existing law (34 Stat. 596, 606-607).

In other words, Puerto Rican citizens were no longer required to renounce an allegiance to a sovereign in order to comply with the naturalization requirements. In addition, unlike aliens residing in Puerto Rico who could naturalize in the U.S. District Court for Puerto Rico, Puerto Rican citizens could count their residence in Puerto Rico as residence in the United States but were required to travel to a state or and incorporated territory to undergo the naturalization process in a federal district court. For the purposes of the BINA of 1906 Puerto Ricans were treated as white aliens, eligible to naturalize under special circumstances. As public naturalization records available in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) show, many Puerto Ricans residing throughout the United States took advantage of this law.

In 1914, Congress amended the BINA of 1906 and provided Puerto Rican soldiers serving in the U.S. Revenue-Cutter Service (Coast Guard), Navy and Marines the ability to treat their years of service as a form of residence in the United States for naturalization purposes. Soldiers serving in the U.S. armed forces were not required to be citizens and Puerto Ricans had been enlisting in large numbers since 1898. The Naval Service Appropriations Act of 1914 (NSAA) provided that:

Any alien of the age of twenty-one years and upward who may, under existing law, become a citizen of the United States, who has served or may hereafter serve, for one enlistment of not less than four years in the United States Navy or Marine Corps, and who has received therefrom an honorable discharge or an ordinary discharge, with recommendation for reenlistment, or who has completed four years in the Revenue-Cutter Service and received therefrom an honorable discharge or an ordinary discharge with recommendation for reenlistment, or who has completed four years of-honorable service in the naval auxiliary service, shall be admitted to become a citizen of the United States upon his petition without any previous declaration of his intention to become such, and without proof of residence on shore, and the court admitting such alien shall, in addition to proof of good moral character, be satisfied by competent proof from naval or revenue-cutter sources of such service: Provided, That an honorable discharge from the Navy, Marine Corps, Revenue-Cutter Service, or the naval auxiliary service or an ordinary discharge with recommendation for reenlistment, shall be accepted as proof of good moral character: Provided further, That any court which now has or may hereafter be given jurisdiction to naturalize aliens as citizens of the United States may immediately naturalize any alien applying under and furnishing the proof prescribed by the foregoing provisions (38 Stat. 392, 395).

This provision treated Puerto Ricans and other insular-born soldiers as aliens for naturalization purposes. The new amendment made it possible for Puerto Rican soldiers to use their military service as a vehicle to acquire a U.S. citizenship via naturalization.

It is important to note that in 1915 a Federal District Court in Maryland affirmed the ability of Puerto Rican soldiers to treat their military service as a vehicle to naturalize. Socorro Giralde, born in Fajardo, Puerto Rico and recently honorably discharged from the U.S. Revenue-Cutter Service, submitted a petition for naturalization in a U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland. Subsequently, in In Re Giralde (1915) the Federal government challenged his petition arguing that Puerto Ricans were not aliens for the purposes of the NSAA of 1914. Writing for the Court, Judge John C. Rose rejected this challenge on four grounds. First, Judge Rose argued for a loose interpretation of the word alien that could include Puerto Ricans. Second, Judge Rose argued that the Supreme Court established in Gonzales that Puerto Ricans were racially eligible to naturalize and acquire a U.S. citizenship. Third, while he acknowledged that the U.S. military did not have a general citizenship requirement, Judge Rose argued that the intent of the law was to enable the naturalization of non-citizens who both “faithfully served the flag” and were qualified to become citizens. Citizenship, Judge Rose noted, was also a precondition for “increased pay.” Finally, Judge Rose concluded that if the BINA of 1906 enabled Puerto Ricans to acquire a U.S. citizenship, why would the NSAA of 1914 bar Puerto Rican soldiers from naturalization?

Citizenship Through Individual Naturalization

In sum, individual Puerto Ricans were eligible to naturalize and acquire a U.S. citizenship more than a decade before the enactment of the Jones Act of 1917. During this period, birth in Puerto Rico was tantamount to birth outside of the United States. As Secretary of War Stimson suggested in 1912, both the BINA of 1906 and the NSAA of 1914 made it possible for individual Puerto Ricans to naturalize in order to acquire a U.S. citizenship. A survey of available public naturalization documents demonstrates that Puerto Ricans were using these laws to naturalize and acquired a U.S. citizenship long before the enactment of the Jones Act of 1917. These naturalization laws were anchored on the Naturalization Clause of the Constitution. Puerto Ricans who acquired their U.S. citizenship via naturalization prior to 1940 were treated as naturalized immigrants for purposes of the prevailing immigration and naturalization laws.

Cited and Suggested Resources:

Primary Sources

Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1906, Pub. L. No. 59-338, 34 Stat. 596 (1906).

Civil Service Act of the United States, ch. 27, 22 Stat. 403 (1883).

Jones Act of 1917, Pub. L. No. 64-368, 39 Stat. 951 (1917).

Dastas Garrosi v. Garrosi, 1 PR Fed. 230 (1904).

Echcandia v. San Sebastián, 9 PR Fed. 153 (1909).

In re Giralde, 226 F. 826 (1915).

Insular Passports Act of 1902, Pub. L. No. 57-158, 32 Stat. 386 (1902).

Martínez de Hernández v. Casañas, 2 PR Fed. 519 (1907).

Naval Service Appropriations Act of 1914, Pub, L. No. 63-121, ch. 130, 38 Stat. 392 (1914).

United States Congress. Senate. Declaring that all Citizens of Porto Rico and Certain Natives Permanently Residing in Said Island Shall be Citizens of the United States: Hearings on H.R. 20048, Before Senate Comm. on Pacific Islands and Porto Rico, 62nd Cong., 2d sess., 1912.

Secondary Sources

Bothwell, Reece B. Trasfondo Constitucional de Puerto Rico: Primera Parte, 1887-1974. Rio Piedras: Editorial Universitaria, 1971.

Charlton, Paul. “Naturalization and Citizenship in the Insular Possessions of the United States,” Annals of the American Academy of Political Science (30) (1907): 104-114.

Gettys, Luella. The Law of Citizenship in the United States. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1934.

Van Dyne, Frederick. Citizenship of the United States. New York: The Lawyer’s Cooperative Publishing Co., 1904.

Vega, Bernardo. Memoirs of Bernardo Vega: A Contribution to the History of the Puerto Rican Community in New York. Edited by César Andreu Iglesias. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1984.

Venator-Santiago, Charles R. “Extending Citizenship to Puerto Rico, The Three Traditions of Inclusive Exclusion, CENTRO: Journal of Puerto Rican Studies,” 25(1) (2013): 50-75.